Hi {{first_name|there}}!

Yesterday, we hosted the final online run of the NR4W experiment. Thank you, Chris Federer! Now, we’d like to share one thing we’ve learned.

In Brief:

The Original Goal: We wanted a Goldilocks challenge statement to use in our brainstorming and creative problem-solving experiment – something real, meaningful, and complex – yet also approachable for anyone who might participate.

The Approach: Many rounds of crowdsourcing, expert interviews, and rich visuals all eventually led to a single, simple question.

The Takeaway: Creativity loves constraints, but sometimes, constraints kill creativity. The framing matters.

Experiments vs “Real” Life

It's still far too early to say what the data shows. We have lots of questions, with answers to be revealed in time (and at the upcoming gathering).

We can, though, talk about what we've learned as practitioners.

This experience changed us. We think about meeting design and facilitation much differently now than we did 18 months ago.

We also have a lot more empathy for our academic colleagues who strive to run controlled research studies on inherently messy subjects like team collaboration.

When we began this work, we asked

"What if we (academics and practitioners) worked together? How might we run an experiment that studied the kind of sessions a trained facilitator might run?"

Previous studies used processes that we believed to be unduly constrained, artificial, and as a result, irrelevant to real business. Our intent was to run an experiment that looked more like what we'd do with clients in "real life."

Of course, a lot of what we do in real life is about adapting to the needs and dynamics of the group. Collaboration practitioners aspire to liberate rather than constrain.

Real Life:

Work with groups to identify solutions to challenges they care about and that relate directly to their work

Spend time exploring the challenge, answering questions, and warming up to the topic, ideally well in advance of the workshop.

Moving to Experiment World (by DALL•E)

Moving to Experiment World:

We needed the same challenge for many groups, so we could compare their solutions.

Teams needed to be comfortable sharing their solution ideas with researchers and the public. This meant the challenge couldn't touch too closely on any sensitive, private, or industry secret questions.

The meeting host follows a script. Answers to questions would be decidedly off-script, introducing unwelcome variables. That's a no-go.

Since everyone volunteered and we didn't share the topic in advance, there was no guarantee that anyone involved would have the expertise needed to answer questions.

Volunteers agreed to no more than 90 minutes. This left no time for deep consideration of the problem.

In short, experiments like this one seek to control as many variables as possible, which renders adaptive facilitation skills largely irrelevant. Instead, we had to focus on designing a meeting where the process itself could simulate what a facilitator might do.

How We Found Our Challenge Topic

If you attended the January Symposium, you may remember presentations from people working to make the world a better place. (Missed it? Access the recordings when you register for next year's Gathering.)

The goal was to crowdsource a topic related to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, a natural anchor in our search for a meaningful, complex, and globally relevant challenge.

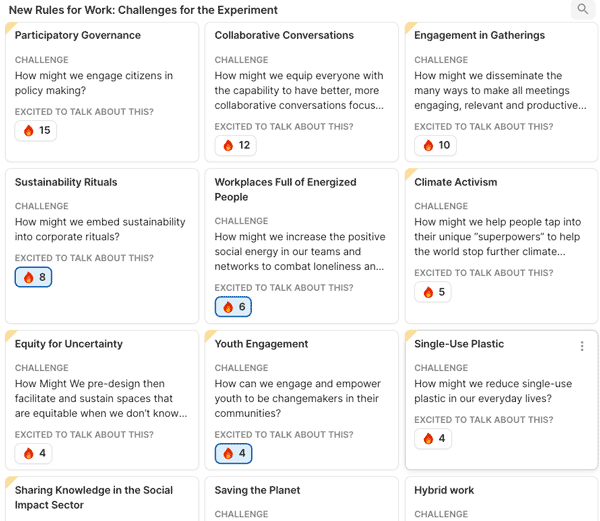

Here's what folks came up with.

Pilot Experiments

Based on the crowdsourcing work and conversations with our advisors, we settled on three final challenges.

How might we bring unheard voices into the places where decisions are made?

This was a refinement of the top-voted Participatory Governance challenge, suggested by the person who entered that idea.

How might we be more integrated as a whole while simultaneously operating more autonomously?

Keith McCandless offered this wicked-question reformulation of the challenges around collaboration, engagement, and hybrid work. This version highlights the underlying tension behind these challenges.

Thinking about lonely offices, retail spaces, and other commercial buildings, what are some creative alternative uses for underutilized commercial buildings that might help solve one of the world’s big problems?

The entire project was inspired by the return-to-office debate, and this challenge gave us a concrete way to talk about what should happen to the office when teams don't regularly work there.

We then worked with domain experts and the illustrator Lisa Rothstein to build out short challenge briefings for participants. Here's the illustration for the lonely building challenge.

Take a look at the complete briefing and you'll see details about potential stakeholders, design constraints, and what an ideal solution would achieve. Solid, succinct problem framing!

We hoped that providing this detail would make up for our inability to talk about the challenge with groups in advance.

Then, we started testing.

We decided to start with the lonely buildings challenge because we felt it would be easiest for us to tell whether the process was resulting in creative solutions. (Our plan was to move to the other challenges once we knew we could get at least 50 solutions for each. Sadly, we didn't manage quite that many experiments.)

Guess what happened?

After the first 15 small group presentations, we noticed a pattern.

And by pattern, I mean this. All the solutions were basically the same.

🤦♀🤦♂

"Ha ha! You guys killed creativity!"

Nearly every group proposed a multi-use space for community living + work.

It's obvious, really. 20-20 hindsight is annoying that way.

Knowing what we know now, you can see how the Challenge Briefing demands the creation of multi-use spaces.

Buildings have many rooms, which means they can serve more than one function.

Different community stakeholders have different needs.

Keeping everything within easy walking distance advances many sustainable development goals by reducing energy consumption, road congestion, access challenges, and more.

Sadly, this answer was neither creative nor compelling.

Even the teams suggesting these rehab + work skills training + aquaponics farm + quaint lunch spots didn't seem like they'd want to visit such a place.

We told our advisors what we'd seen.

They laughed.

A lot.

And they were right. We killed creativity. By trying to make up for our crunched time, we attempted to backfill all the problem-framing steps with a detailed brief.

It's said that creativity loves constraints. I now wonder if that's a bit of propaganda on constraint's part because it sure seemed like creativity would prefer a more casual relationship.

Our advisor and creativity expert Roni Reiter-Palmon, PhD dispelled some other nasty rumors about creativity.

She told us that:

True creativity is rare.

We'd been told that everyone is creative. Maybe that's true in some sense, but it sure wasn't in our experiment or in the wider creativity research. Looking back, our practice didn't necessarily reflect this either. We've run lots of workshops where folks walk away happily hugging their beige ideas.

Experts are more likely to have creative ideas than others.

We'd been told that great ideas often come from unlikely sources. While newbies sometimes bring a refreshing perspective, they don't know what they don't know. Their suggestions are more likely to be predictable and simplistic.

Given the overly constrained briefing and our experiments full of novices, it looked like we were poised to generate quite the yawnfest.

A Challenging Choice Regarding the Challenge

Should we continue with the briefing as it was, and hope creativity found its way free from the cage we'd put it in?

Or should we simplify the briefing in an effort to unleash creativity, at the risk of not having enough data?

Due to a host of factors, it was becoming difficult to recruit experiment teams.

Like I said before, we really wanted at least 50 proposals in response to each challenge. We weren't going to get as many volunteers as hoped, and we weren't sure whether an updated brief would make a difference.

What's your coolest, most exciting idea?

After much deliberation, we decided to simplify the challenge.

The new "briefing" consisted of a single sentence.

Thinking about lonely offices, retail spaces, and other commercial buildings, what are the coolest, most exciting uses for these empty spaces?

And you know what?

It worked.

Woo hoo! Fly free, creativity!

We still saw proposals for multi-use community spaces, but they were more varied. More importantly, they weren't alone. We now have lots of ideas for these lonely spaces, and some of them are pretty darn cool!

(We'll share highlights during the upcoming Gathering. Early bird tickets are available now.)

The Lesson: Framing Matters

Yes, duh, I know, you know, of course... but OH MY GOODNESS!

Framing really, really matters.

When we altered the framing question, the experiment results changed.

No other factor created such a noticeable result. The location, the tech, the number of people, the process variation, the weather, the group's ease with each other... none of these factors seem to make an obvious difference in the quality of final proposals.

The starting question absolutely did.

Framing - the act of deliberately setting the context for a group – determines the information the group considers, and what it ignores.

Whenever you are trying to get people on the same page, with common goals and a shared appreciation for what they’re up against, you’re setting the stage for psychological safety. The most important skill to master is that of framing the work.

Before the experiment, we knew that it was important to thoughtfully consider the frame.

For me, this experience greatly magnified that importance. I now wholeheartedly agree with Dr. Edmondson when she suggests framing is a leader's most important responsibility.

This raises critical questions:

How do you notice and understand the framing set for any given situation?

How do you identify a more useful frame?

We had the great fortune to repeatedly witness brilliant folks rendered dull by an inappropriate frame. This made it easy to answer these questions for the experiment.

The experience made it easier to see framing in other situations too, and led to the development of a way to visualize common framing patterns. I'll share more about that in the next few articles.

For now, THANK YOU to everyone who participated in the experiment!!! 🎉

We're done with online sessions, and we have just a few private groups bringing in the final in-person sessions. We'll share more of our practitioner insights in the weeks to come, and look forward to seeing you at next January's Gathering.

- Elise & Dave

New Rules for Work Hosts

Did you find this useful? Know someone else who might enjoy it?

Please forward, share, subscribe, and help us spread the word. Thank you!

Ready to work with us? Let’s talk.