Last time, we shared how our experiment drove home the importance of framing. Framing - the act of deliberately setting the context for a group – determines the information the group considers, and what it ignores.

In many ways, the frame determines what's possible.

Today, we'll explore this idea further by looking at how framing impacts the way we approach meetings.

BLUF

Experts and researchers all look through their own frames. Identifying an expert’s frame helps clarify their motives and who can benefit from their advice.

Regarding meetings, the most popular frames appeal to the largest audiences - namely employees and individual contributors. Unfortunately, these frames are not as useful to organizational leaders, who are in the best position to make changes.

When we plot the frames used to talk about meetings across multiple dimensions, it becomes easier to spot potential issues and proactively select more useful frames.

Adam Grant and Mary Poppins

I recently read Adam Grant's book Think Again. It’s about questioning ideas, learning and relearning, and coming at problems from new angles. In other words, it's a book about framing and the importance of reframing.

So you can imagine my unhappy surprise when people began forwarding this LinkedIn post to me.

Hate, worst, suck. Hmm.

Let's imagine the potential universe of directions from which we might approach the topic of meetings.

Image not to scale

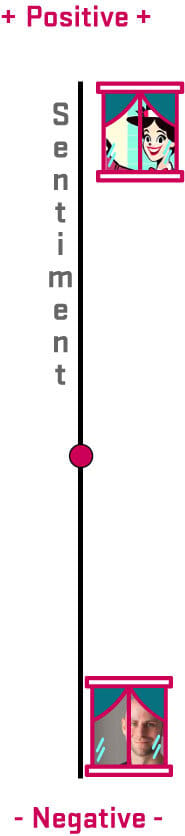

Adam Grant’s perspective is decidedly negative.

Looking at Meetings Through a Negative Frame

I spent an afternoon reviewing the comments on the LinkedIn post above, and here's what I saw:

There weren't many stories about awful meetings. Of those shared, most were about asshats– really terrible people abusing their colleagues.

None of the stories I saw were about meetings led by the person who added the comment.

In other words, the stories detailed other people's bad behavior and terrible personalities, and bad meetings organized and run by other people.

Then, he asks "What's your favorite way to make meetings not suck?"

Hopefully, you can spot the problem there.

This second question was met with lots of advice copied from clickbait articles.

For example, commenters proclaimed "No agenda, no attenda!" (Seriously, does anyone actually do this? If so, are they the asshats?)

"Meetings suck" is not a novel frame, which is disappointing.

What if Mr. Grant were to take his own advice and think again?

Looking at Meetings Through a Positive Frame

I think of the "Meetings are fun!" frame as the Mary Poppins window, because:

You find the fun and, Snap!, the job's a game!

Intercating with Mary is hoot!

These frames sit at opposite ends of the Sentiment spectrum, inviting very different stories.

While Mary Poppins makes me smile, she isn't known for her work in organizational design or meeting effectiveness.

So let's look at other people who look at meetings through a positive frame.

Priya Parker's The Art of Gathering is beloved by many for its rich stories about meetings that change peoples' lives. From Ms. Parker's window, each meeting presents an opportunity and responsibility for connection, meaning, and joy.

Shishir Mehrotra collects stories from the startup and tech world. C-suite executives gather around the table and proudly recount the clever strategies they've designed to ensure their business-critical meetings work well and nurture their company culture. Shishir's book on these Rituals of Great Teams is forthcoming, and you can preview the many great meeting rituals here.

Daniel Coyle's Culture Code isn't a book about meetings per se. Rather, it's a book about wonderful business cultures that happens to be full of meeting stories. Mr. Coyle's frame raised the question "What do people in great company cultures do?" and that frame invited stories about great meetings.

Culture Code is just one example of a book about what works well – positive framing – featuring excellent meeting examples. Amy Edmondson, Brené Brown, Patrick Lencioni, Frederic Laloux, Markus Buckingham, Peter Drucker, David Marquet, Jim Collins - pick up any popular business book about what works well written in the last 50 years and you'll find stories about great meetings.

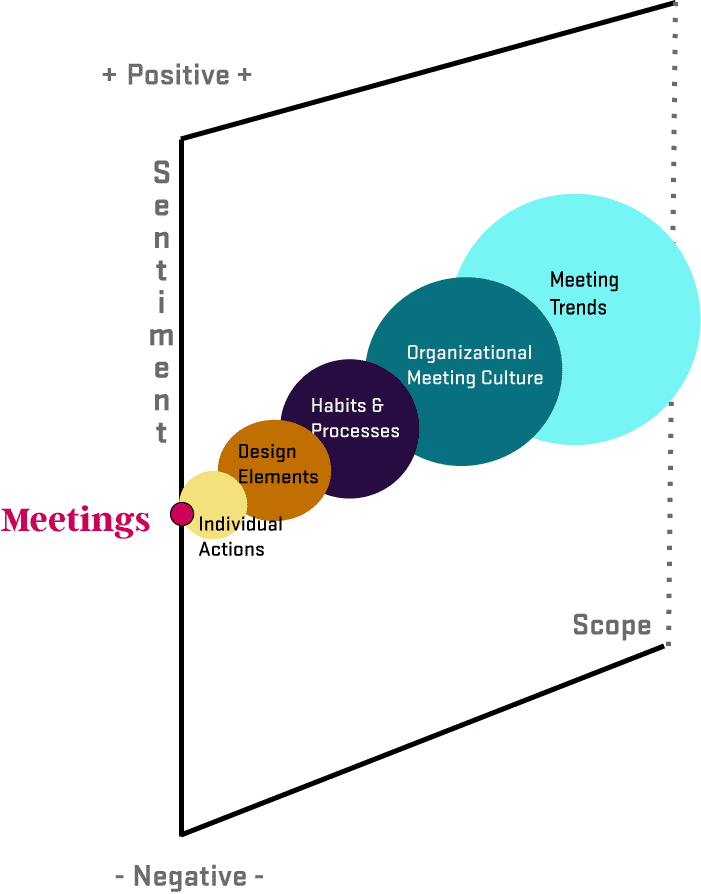

Changing the Frame's Scope

In our search for positive takes on meetings, we can see another dimension to framing.

The topic of "meetings" is pretty vague. An article or study about meetings could center on any (but not all) of the following:

Individual Actions (and reactions)

Who interrupts who? When do people engage? How do they deal with conflict? How do their biological reactions (brainwaves, pupils, heart rate) respond to different meeting scenarios?

Conversational analysts, human performance researchers, and AI-based sentiment reports are all about these measurable micro-moments.

Meeting Design Elements

Was there an agenda? An icebreaker? A PowerPoint presentation? How did the meeting's location and tech impact the group? How long did it last?

Meeting scientists, tech companies, and facilitators often focus here, looking for ways to optimize the design of individual meetings.

Meeting Habits and Processes

How does a team meet over time? What meetings are held as part of a process - product development, hiring, or strategy, for example?

This is the frame for process experts, team leaders, and functional group managers. This is also where you see terms like "ritual," "working agreements," and "communication plans" dominate the conversation.

Organizational Meeting Culture

What are the norms and expectations across this organization? How does this company's DNA show up in their meetings?

If you've ever read stories about meetings at Amazon, Pixar, or the ancient Greek senate, you've looked at meetings through the sociologist's frame. From this vantage:

It is argued that meetings exist within a sociocultural system, but they also play a major role in shaping this system, as they both create and then respond to the context that they have generated. Meetings provide individuals with a way to make sense of as well as to legitimate what otherwise might seem to be disparate talk and action, whereas they also enable individuals to negotiate and validate their relationships to each other. Finally, I suggest that meetings are a form that frequently stabilizes but can just as easily destabilize and transform a cultural system in ways that are often unrecognized and even unintended by actors in the system.

Large-Scale Meeting Trends

How many meetings are there around the world? Are more teams using video conferencing? How much time does the average CEO spend in meetings, and how does this differ by industry, country, or company size?

Journalists, marketers, and analysts love this frame. So do all the experts working at other frames, because this is the one that gives us handy data tiddlings to stick in our articles.

After all:

9 out of 10 readers find articles including statistics more persuasive.

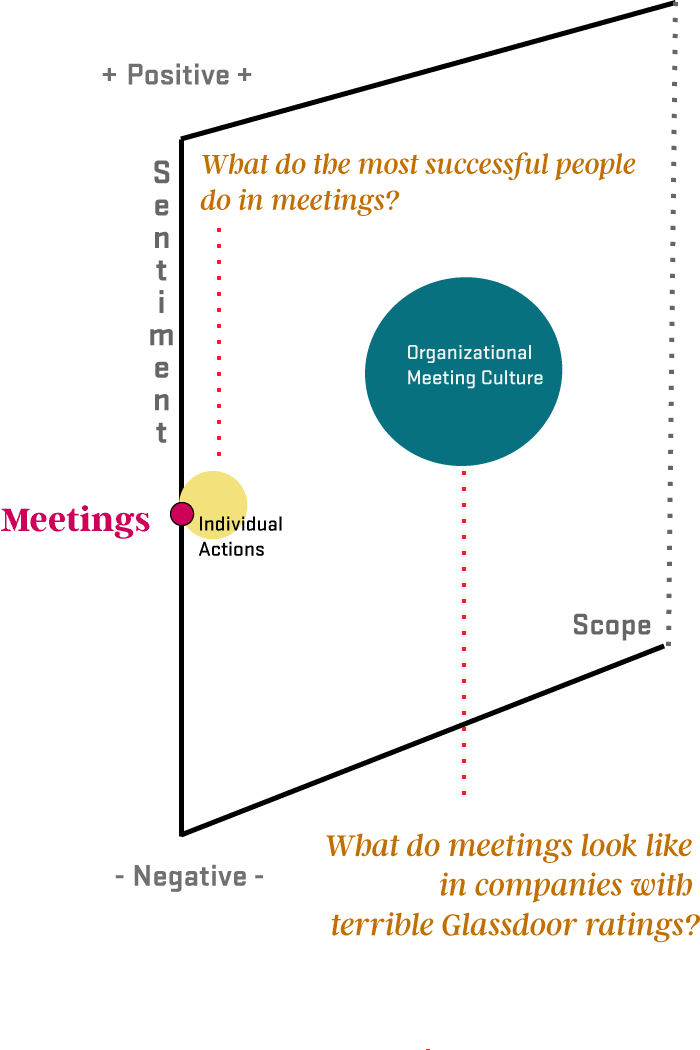

Now, when we consider the possible frames across these two axes, we get a host of new potential frames. For example:

What do you do with this? It depends on your frame.

Our topic is meetings, and you want to know "What can you do about meetings?"

This depends on who "you" are, and asks us to consider another set of possible frames.

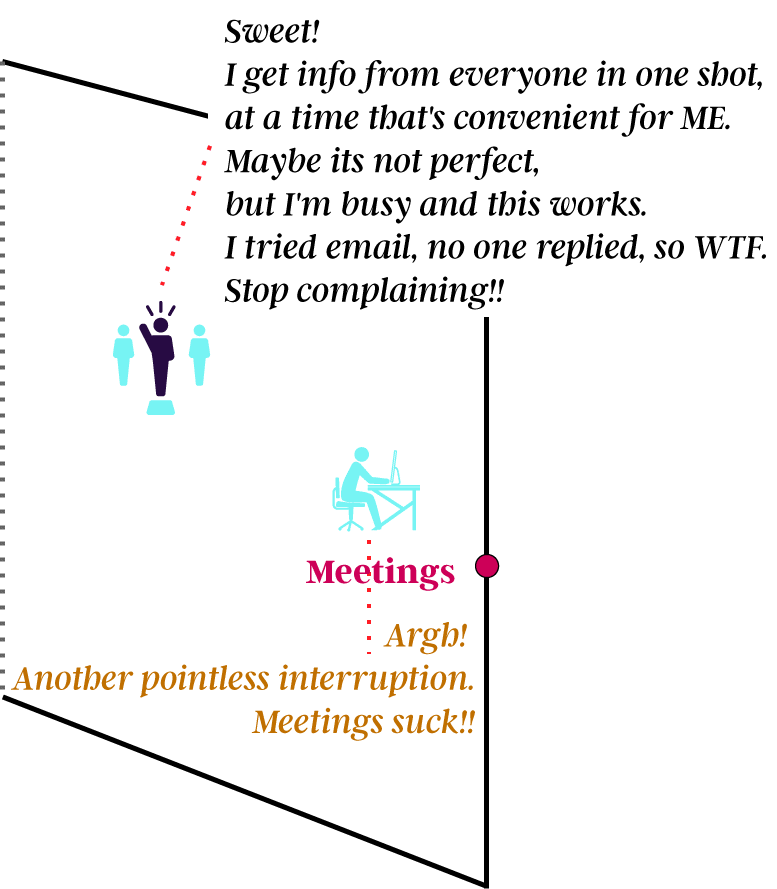

A meeting may look very different to the leader who scheduled it versus the individual contributor who has nothing to say and a ton of work to do.

Let's revisit Adam Grant's Work Life podcast episode.

Mr. Grant wisely ignored most of the advice he received on LinkedIn. The episode was released in September 2023, and in my (very informed) opinion, the advice is solid!

For people worried about too many ineffective meetings draining productivity, this episode shared interventions they could try.

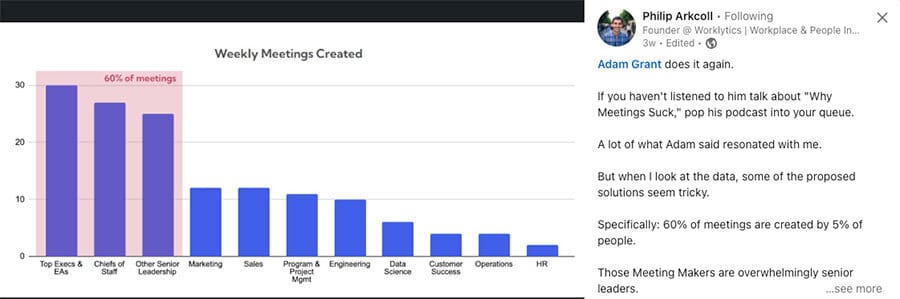

As Philip Arkcoll from Workalytics pointed out, this advice was targeted at leaders.

People invited to meetings have a harder time changing those meetings. They can, but it takes incredible courage. From their frame, speaking up looks pretty risky.

People scheduling, designing, and hosting meetings have lots of options.

Senior executives and leadership experts have all the options! Of course, they frame their priorities around other topics. Meeting effectiveness rarely appears in the window of things they need to care about.

Meetings? Dude, I have other things to worry about.

Most leaders don't usually look at the world through the "my meetings suck" frame. They believe their meetings are fine – or at least no worse than anyone else’s. This is known as the leader's blind spot, a phenomenon that's been repeatedly verified by meeting, leadership, and neuroscience studies.

Looking at stakeholder frames invites us to consider how meetings look from other people's point of view – in other words, to empathize – and then tailor our advice accordingly.

The Framing Failure that Perpetuates Lousy Meetings

Now let's put these framing dimensions together, because I think they provide insight into why the "meetings problem" is so darn intractable.

Adam Grant is no dummy.

He knows that claiming that "meetings suck" will attract a metric ton of clicks, and since part of his job is to get all the clicks, leading with Why Meetings Suck makes a bucket of good sense. And clicks!

He's not the first. If you're writing about meetings and want to get a lot of readers or sell a lot of books, use a negative frame. Meetings Suck and Death by Meeting are bestsellers.

"Meetings suck" is a (Sentiment: Negative) frame typical of (Stakeholder: Individual Contributors) who then tell stories about the awful behavior of other people (Scope: Individual Actions/Reactions) or of meetings that lack relevance and agendas (Scope: Meeting Design Elements).

I suspect Mr. Grant also wants to share great advice, and if you want to help folks fix meetings, you talk to leaders. Of course, this asks the listeners to adopt different frames.

The advice ranges from carefully considering the best approach (Sentiment: Positive) for a meeting's timing and invite list (Stakeholder: Meeting Organizer, Scope: Meeting Design Elements) – to reestablishing team meeting norms (Stakeholder: Manager+, Scope: Meeting Habits/Processes) – to canceling all internal team meetings across a company (Stakeholder: Executive, Scope: Organizational Culture).

Which all probably falls flat for the (Stakeholder: Individual Contributor) audience it attracts. The framing that brings the largest number of clicks isn't connecting with the folks who can do something about the problem.

Lest we abandon hope, I have seen companies make great improvements to their meetings, but only when they start with a different frame.

When leaders get excited about improving workplace culture or productivity, the meetings get swept along for the ride. You'll find the best stories about how to do meetings well in books about team agility, organizational culture, innovation, and the like, where the whole topic gets reframed as part of something desirable and achievable.

This is why the first piece of advice in my book about meetings is to stop using the word "meetings”! The universe parked a bag of nasty in front of that frame, so we're better off heading to where we can get a clearer view.

Finding Useful Frames in the Universe of Infinite Potential Frames

In this article, we looked at possible ways of framing the topic of meetings. We used meetings as an example, but you can consider any topic from these frames.

We considered three possible dimensions:

Sentiment: the positivity or negativity of the frame

Scope: the specific focus and scope of the frame, from micro to macro

Stakeholder: the people, roles, or entities that may see the topic differently

Over the past year, I've been digging into the concept of framing, trying to find ways to make it easier to notice frames and select more useful frames. While there are probably countless possible dimensions, I've found these three most useful.

Well, these three and one more.

I'll share more about that fourth dimension next week and will show how to use it by plotting different creativity and strategic thinking activities on the Framing Tesseract.

Until then,

Elise & Dave

What did you think of this email?

About this Publication

In the New Rules for Work Labs project, we delve into the evolving world of team collaboration. We're all about understanding the big ideas, the stories and research behind them, and their application, then pinpointing the Minimal Valuable Collaboration (MVC) approach that offers the most significant impact.

Subscribe for insightful articles, golden collaboration tools, revealing interviews, and exclusive event invites as we embrace a new kind of teamwork – in love with humanity, liberated by tech, comfortable with complexity, and super duper efficient.

Ready to work with us? Let’s talk.