For the past 25 years, I've focused on ways to make collaborative knowledge work easier and more rewarding. While I've learned many fabulous ways to improve collaboration, I've also frequently been frustrated by unintended consequences. I specialize in the interconnected practices of meetings, decision making, and team collaboration, but lack expertise in other areas of my clients' operations. Every truly excellent thought leader and business expert I know has a similar range, with great depth in some practices and lots of stuff they wisely refrain from commenting on.

The challenge is that what we do ripples.

The Ripple Effect: Interdependence in Living Systems

In nature, when wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park, they appeared to trigger a series of ripples that reshaped the landscape.

Wolves helped control deer populations, allowing vegetation to recover, which improved soil health and water flow. At least, that’s one version of the story. Other scientists say it wasn’t just the wolves—other environmental factors were at play too. The trophic cascade celebrated in the famous video above paints a simple - and oversimplified - description of how small shifts in interconnected and interdependent natural systems like this can have large, maybe hoped-for, but ultimately unpredictable impacts.

Now, apply this idea to organizations. Imagine your organization wastes way too much time in unproductive meetings, so the leadership team decides to ban all internal meetings. Problem solved, right? But just like in nature, this one change can create unpredictable ripples. Without those meetings, communication often slows, collaboration weakens, and decision-making gets messy. Teams that once relied on regular check-ins now scramble to find new ways to stay aligned, often leading to endless email chains and distracting Slack messages—and we all know how that goes.

Companies that try meeting bans often find that it's like pulling dandelions from a garden. You spend all this energy removing them, expecting productivity to flourish, only to see dandelions pop back up—or worse, their absence leaves space for uglier weeds.

Now, I'm not suggesting that meeting bans are all bad. I've seen them work well - but only when they're used in conjunction with changes like better documentation, async communication, and thoughtful meeting design.

Meetings - like all collaborative practices - operate as one piece of an interconnected system. Changing one part of this system impacts other parts of the system.

This is why it’s crucial to see collaborative organizations as living ecosystems. Any change—whether it’s a new tool, a team restructure, or shifting communication norms—ripples through the entire system. The goal isn’t just to fix one piece of the puzzle but to understand how each decision cascades through your organization, influencing culture, productivity, and morale.

I believe we need a simpler way to visualize and talk about this system. Leaders should be able to discern which parts of their systems they’ve intentionally designed and identify areas they can adjust to better achieve their goals.

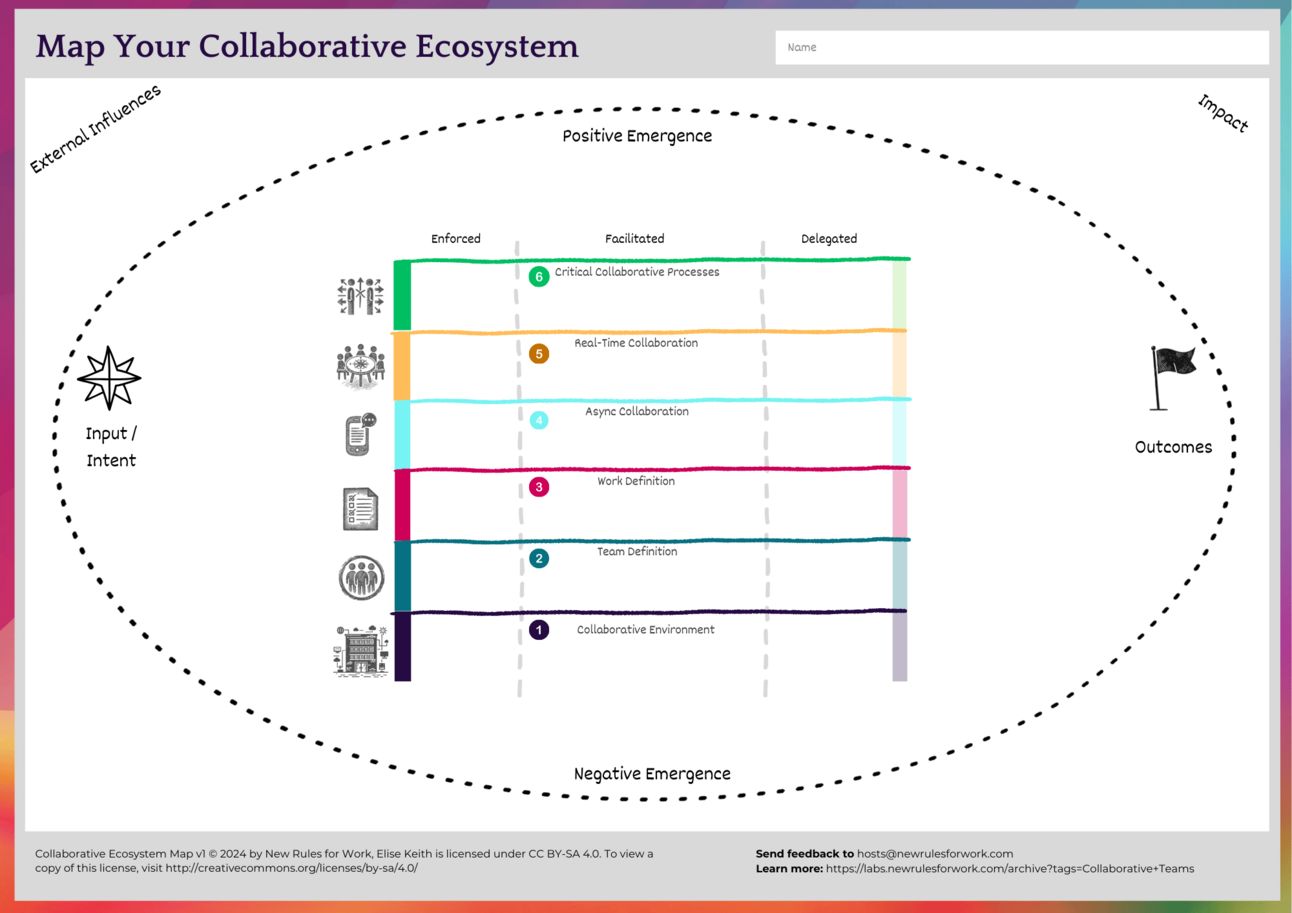

With these objectives in mind, I’d like to introduce version 1 of the collaborative ecosystem map.

The Larger Mission:

Create environments that make it easy and natural to do things in known good ways.

The Collaborative Ecosystem Map isn’t a step-by-step methodology or a set of prescribed practices. Instead, this is a sensemaking tool designed to help leaders anticipate and spot the ripples within their organization. By considering which design choices have been made—team structures, processes, environments— and how they interconnect, you can better understand where things are working and where adjustments might be needed.

Think of this map as a way to see the "what" and "why" of your organization’s dynamics. It helps you identify potential impacts and areas for improvement, but the specific "how" is yours to determine based on what you discover.

Let me walk you through the proposed mapping steps.

Begin with Goals and Context

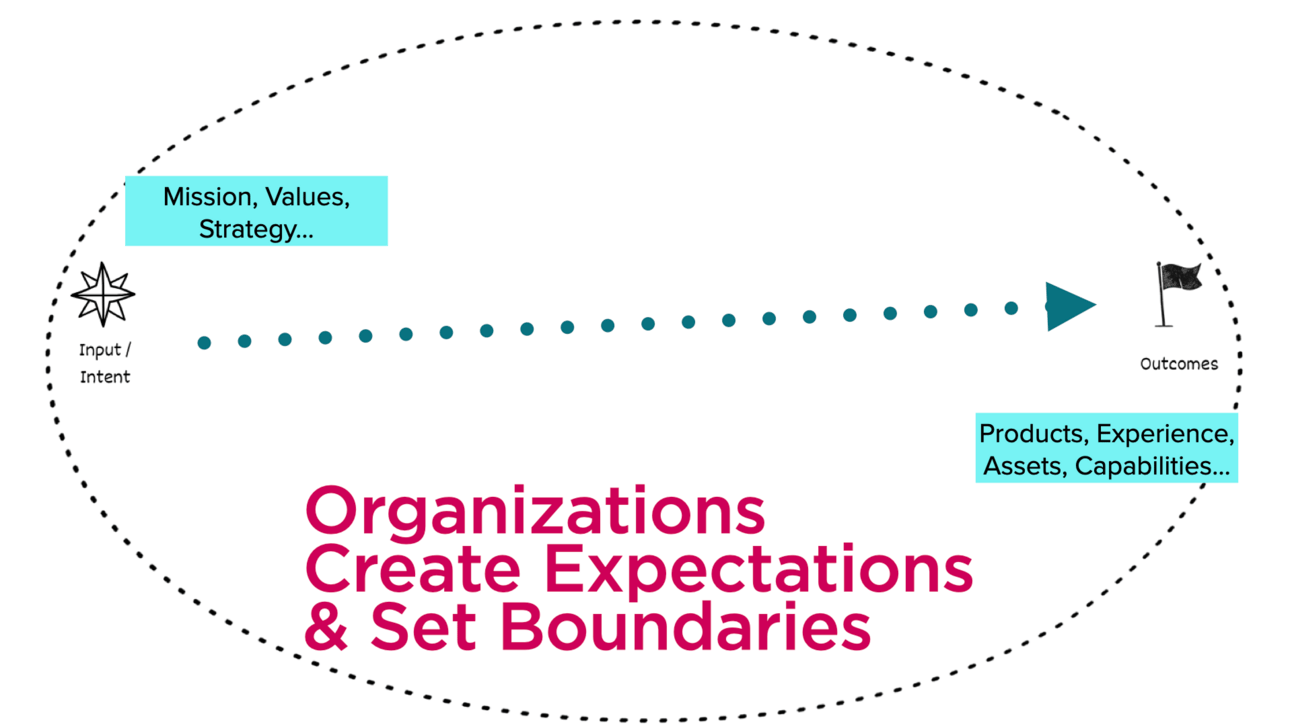

Every organization exists to achieve goals that individuals can't accomplish alone. You operate within a larger context—countries, markets, industries—and you have inputs that must be transformed into outcomes.

The organization creates these high-level expectations and sets the boundaries. Within those boundaries, the work gets done by individual people.

Organizations pursuing multiple goals involving many people must develop systems to direct and coordinate efforts. The formation of teams is one of those systems. As Ashley Goodall said, teams make work meaningful.

Meaning is knowing how you fit in, and feeling confident that your work has some value. Meaning-connecting is one of the signature contribution of teams.

We refer to the interplay between individuals, teams, and these systems as a team’s “Way of Working” (WoW). Your organization may have built its WoW on an externally defined methodology, such as OKRs, KPIs, or Scrum. There are many options available, and your selected methodologies shape how your teams operate.

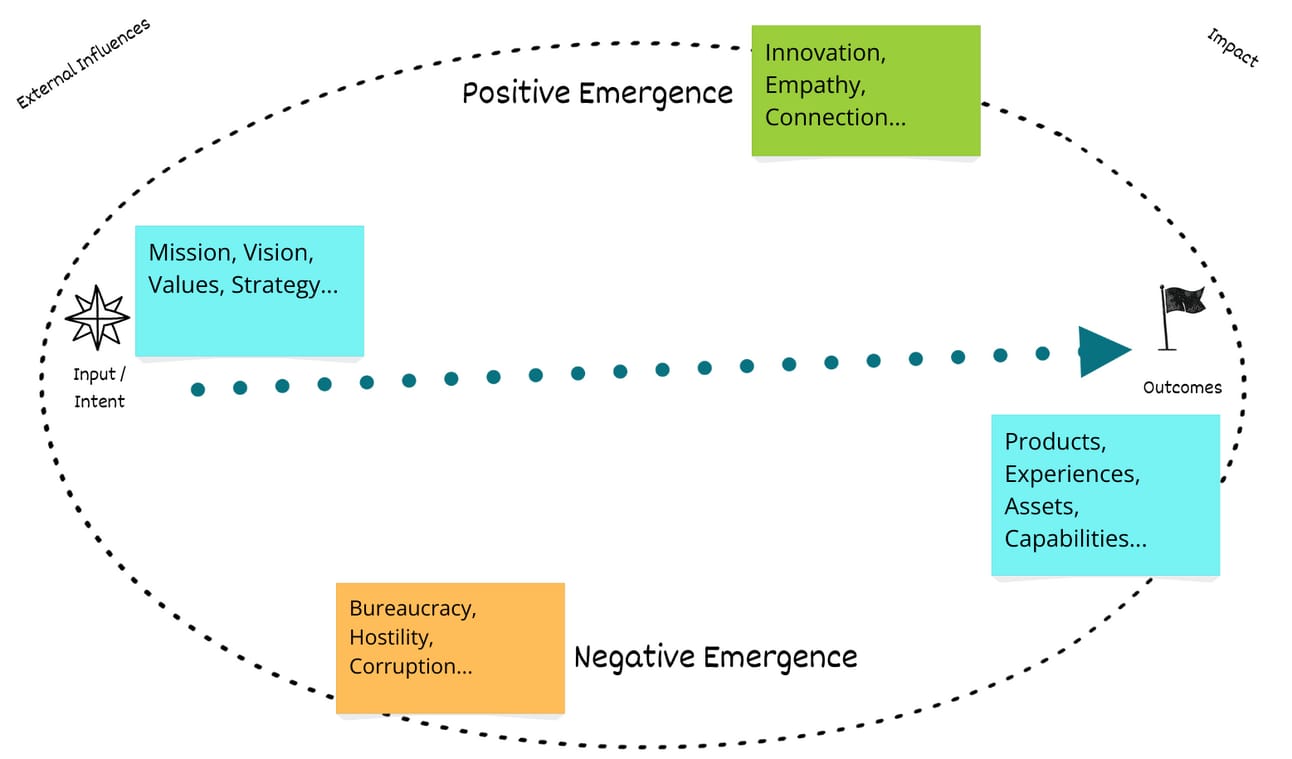

We call the emergent quality of what it's like to work in your organization the "culture." Research abounds regarding the qualities of great cultures. They may be innovative, inspiring, inclusive, reliable, psychologically safe, fun, productive, meaningful, and more. Not all of these qualities can exist simultaneously, of course, because different qualities matter more or less depending on your organization’s goals, and each one requires effort.

Extending the ecosystem analogy, the conditions required for a thriving rainforest differ vastly from those needed for a healthy tundra. We can’t simply declare that one should function like the other, just as we can’t declare ourselves to be innovative, inclusive, or productive without putting in the work. We must collaboratively figure out how to innovate, include, and produce to foster the culture we desire.

Positive cultural qualities emerge from the actions and reactions within organizational systems. Negative qualities can emerge too. Bureaucratic, hostile, inefficient, and corrupt may also describe an organization’s culture, arising from the collective actions of its members.

When you list these elements - the inputs, intended outcomes, the observed and aspirational organizational culture, and surrounding external factors - you're outlining your ecosystem's design goals and constraints.

For this initial exercise, keep it light. Directionally correct is good enough for a first pass.

Now consider: Which of your goals or cultural qualities do you want to focus on first? For example, a recent group of leaders using this map identified their aspiration to create an environment where empathy is expressed, and team members feel comfortable speaking up. Great aspirations!

Next, Evaluate the Designable System

Is your collaborative ecosystem designed to yield these results?

To answer this question, we need to answer three others:

What can we design in the system?

What have we designed?

Are the bits we've designed making it easier for teams to achieve their goals?

We have many known good ways of designing collaborative work. You can design everything from the quality of light on your screen to your future visioning processes. As of 2024, there are over 3 million business management companies eager to advise you, and with AI in the mix, anywhere between 72,000 and 175,000 SaaS apps are at your disposal.

The good news: You have lots of good options.

The bad news: Too many options!

When improving your organizational culture and value-creation systems, you need to focus your efforts and narrow down these choices. You must also be mindful of the complex, adaptive nature of collaborative work—changes in one part of the system ripple throughout the ecosystem.

Your collaborative ecosystem directs the flow of energy and resources between individuals, teams, networks, and systems.

Because we’re dealing with collaborative knowledge work, our systems must adapt to changing demands. Sometimes ideas pour in like rain; other times, there’s a creative drought. Sometimes we need the cleansing fire of risk-taking, and other times, we need predictability.

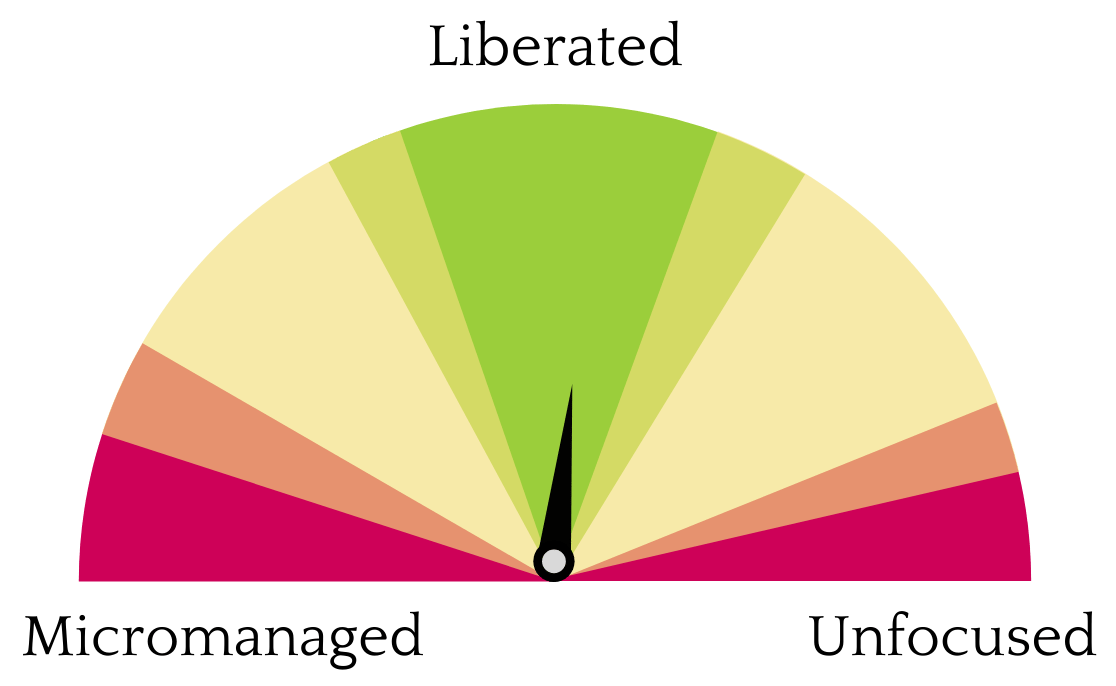

If we leave people to figure out how to turn inputs into outputs without guidance, we risk losing all our energy to unfocused dithering. On the other hand, if we try to dictate every detail of their day, we stifle their creativity. The best systems find that liberating sweet spot in the middle—structured enough to provide clarity and direction, but flexible enough to give individuals the freedom to exercise their gifts.

What specifically are we directing this flow through? What can we design that gives us a better chance of fostering that empathy and psychological safety we're after?

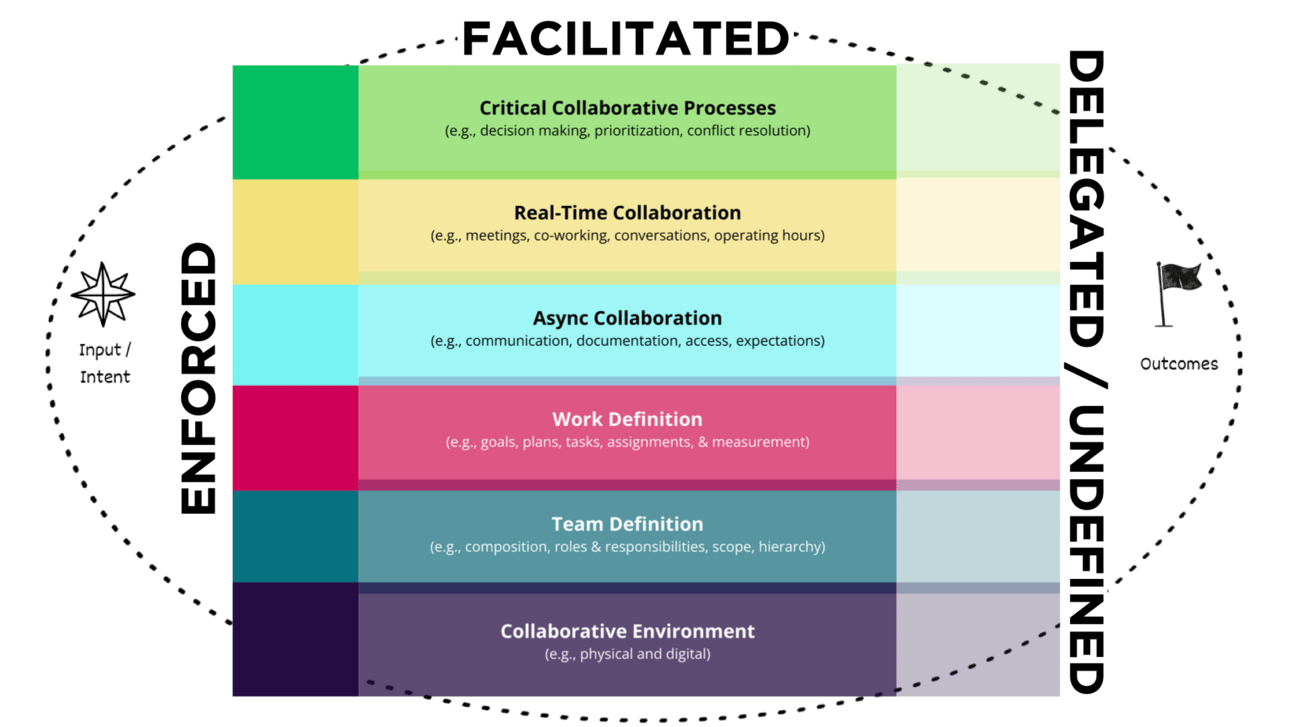

While we could slice and dice this many ways, I suggest focusing on six high-level areas.

1. The Collaborative Environment

And by this I mean the actual physical environment - as in, the office or its digital equivalent.

Example design questions:

Workspace: Where do we work? How is our space organized?

Coordination: Where and when will we work together?

Operating Hours: When can we expect to work with other teams?

Tech: Which tech tools will we use? When and how do we use them? What can we choose for ourselves?

AI: How will we use AI? How will we NOT use AI?

As you craft your answers, think about how you could design the collaborative environment to best achieve your goals. How might it embody and foster the culture you hope to cultivate?

Many companies base their work location decisions on proximity or lease terms rather than on whether their design choices encourage effective collaboration.

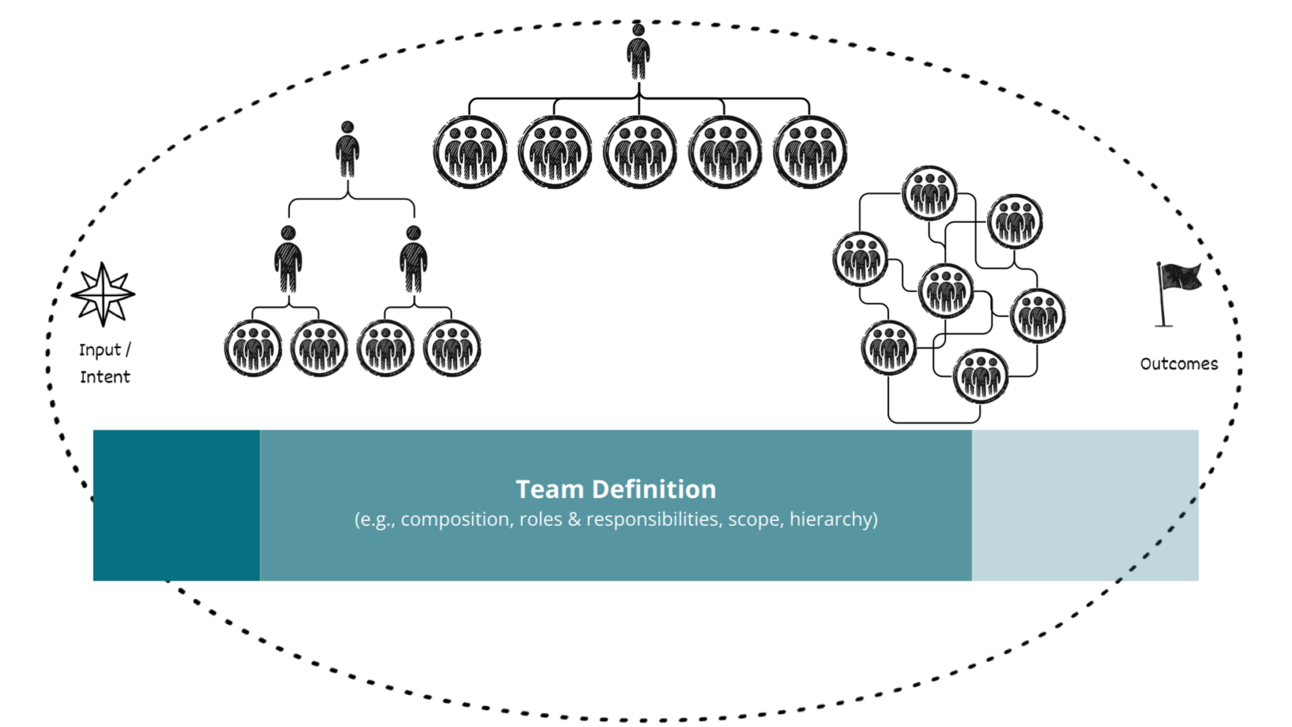

2. Team Definition

How are your teams organized? What kind of teams does your organization support?

Example design questions:

Purpose: What is this team's purpose?

Goals: What does it mean for this team to create value? What does that look like?

Customers: Who benefits from the value we create?

Membership: Who’s on the team?

Roles & Responsibilities: Who does what on this team? Who do we report to?

Areas of Overlap: What do we work on together? What do we work on with other teams?

This is another area where most organizations have answers, although sometimes the answers don't go much beyond an org chart.

3. Work definition

What are we meant to create, what's the plan, and how's it going?

Example design questions:

Requirements: What are we going to deliver?

Plans: What's our schedule or expectation for delivering?

Measurement: How do we measure and evaluate our work?

Status: How will we know what’s being worked on?

It's a pretty good bet that most groups will have a way that they clarify requirements and create plans. In larger organizations, you can also bet that each department does it differently—unless you’ve designed a system that makes it easy to define work in compatible ways. Cue the cross-departmental alignment drama!

NOTE: These first three levels apply to all kinds of teamwork. Henry Ford and Frederick Taylor were all over-optimizing the design of the physical environment, team definitions, and work definitions. Heck, even my family has to figure this stuff out before we can team up to host a big party. This is well-trodden territory, so it shouldn't be a surprise that most organizations have answers to these questions.

For collaborative work, the opportunity lies in ensuring these answers align with your cultural and organizational goals rather than an executive’s personal preferences or status quo defaults.

4. Async Collaboration

How do you work together without talking to each other in real-time?

Example design questions:

Availability: How will we know when a team member is available?

Communication Channels: How will we communicate with each other? Which channels will we use for which messages?

Expected Response Time: When can we expect replies to requests?

Documentation: What do we document? How do we maintain and share documentation?

Standards: Which methods/templates/standards do we use? Where are the guides?

Now we're getting to the parts of the system that don't receive as much leadership love. Setting up Slack or a wiki is a start, but just barely. There's enormous untapped value that's wasted when async collaboration remains undefined and unfocused.

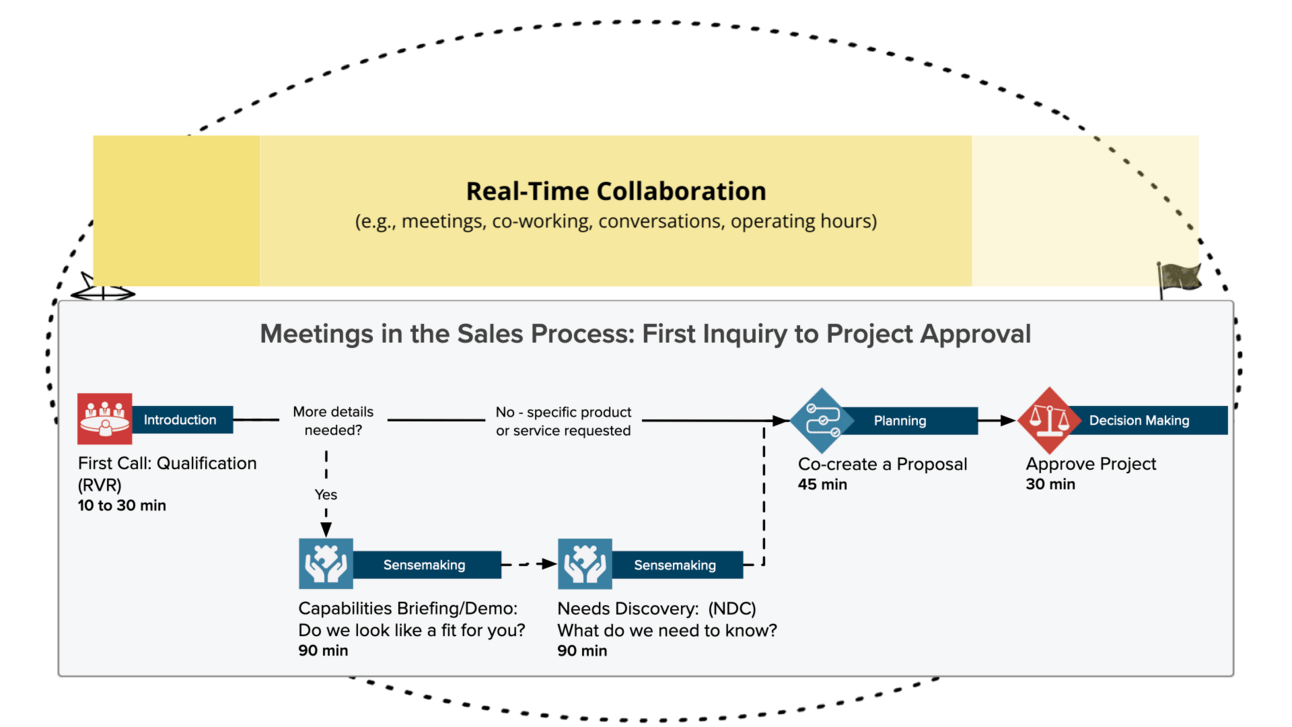

5. Real-Time Collaboration

When and how do we meet and collaborate in real-time?

Example design questions:

Meetings: Which meetings do we need? How do we run them? When?

Focus Time: When will we reserve meeting-free time for concentrated work?

Connection: What will we do to get to know each other?

This is my area of expertise and I can tell you that most organizations do jack-all. If you're interested in what's possible here, get in touch.

6. Critical Collaborative Processes

When we encounter challenges we need to resolve, how will we go about it?

Example design questions:

Candor: How will we share feedback?

Priorities: How do we establish priorities? When and how do we revisit them? What will we always prioritize (even/over)?

Problems: How will we surface issues and resolve conflicts?

Decisions: How will we make decisions?

Victories: How will we celebrate?

Recognition: How will we recognize excellence?

Rituals and the “It Factor”: How do we demonstrate what's cool and important to us?

Friction Fixes: What else do we need to decide to help us work well together?

Finally, we can design how we'll respond to the unpredictable. This level of design is crucial for the success of teams working in high-risk environments and accelerates adaptability for all groups that need to respond to rapidly changing circumstances.

Make it better.

Now you have a more targeted question (or two) and a sense of which parts of your system have room for improvement.

First, reconnect with the larger goal.

The Larger Mission:

Create environments that make it easy and natural to do things in known good ways.

Ideally, your preferred Known Good Ways of working help you achieve your goals and encourage the emergence of your aspired-to culture.

With clear questions in mind and an understanding of where the answers might lie within your organization, it’s time to dig deeper. This could involve doing some research or connecting with a few of those 3+ million companies eager to assist.

You may also find that, now that you have a different way of looking at the system, you already have some answers. For example, after exploring the ecosystem levels, leaders found they had a common language and framework to share solutions. A leader seeking strategies for building empathy discovered how other teams used weekly meetings, lunch breaks, and chat channels to offer and receive support. Another leader seeking more candid feedback learned about one team's suggestion box and another's protocol for running proposal critiques.

When the questions shift from "How can we change our culture?" to "What would our desired culture look like in practice?" and "What can we change in our collaborative environment to make that easier?" the answers get easier too.

Refining Your Implementation

You may notice that the areas listed above are divided into three columns: Enforced, Facilitated, or Delegated. These help us think about how to implement changes.

Enforced

Some Ways of Working are enforced by governing laws, such as those covering access to medical leave or anti-harassment. Others are governed by organizational policies, executive mandates, or standard procedures. Enforcement means actively monitoring and correcting non-compliance.

However, enforcement can be tricky. For instance, the annual "return to the office or else" mandate is a non-liberated approach that often leads to silent (or active) resistance. Hot Tip: Designing a system with the hope that it will make people want to quit is not one of the high-performance strategies endorsed by research. (Obviously!)

This contrasts sharply with remote-first organizations that mandate each department to gather in person at least once a quarter, providing budgets and planning assistance to facilitate these gatherings.

In my experience, mandates regarding safety, legal compliance, and high-level cross-functional standardization prove beneficial. Blanket enforcement of day-to-day collaborative teamwork rarely does.

Facilitated

Facilitating means making the process easy. After deciding which Known Good Ways teams should use, organizations can facilitate their adoption through training, rituals, centralized playbooks, mentors, coaching, and more.

For example, Pixar’s central atrium forces people from different departments to cross paths for coffee and breaks, facilitating creative collisions and cross-functional serendipity. This design naturally supports their imaginative culture and builds the relationships needed to create great films.

Delegated

Finally, if the organization provides no guidance and the team hasn’t agreed on their answers, then you’re effectively delegating these decisions to each individual and trusting that good enough practices will emerge.

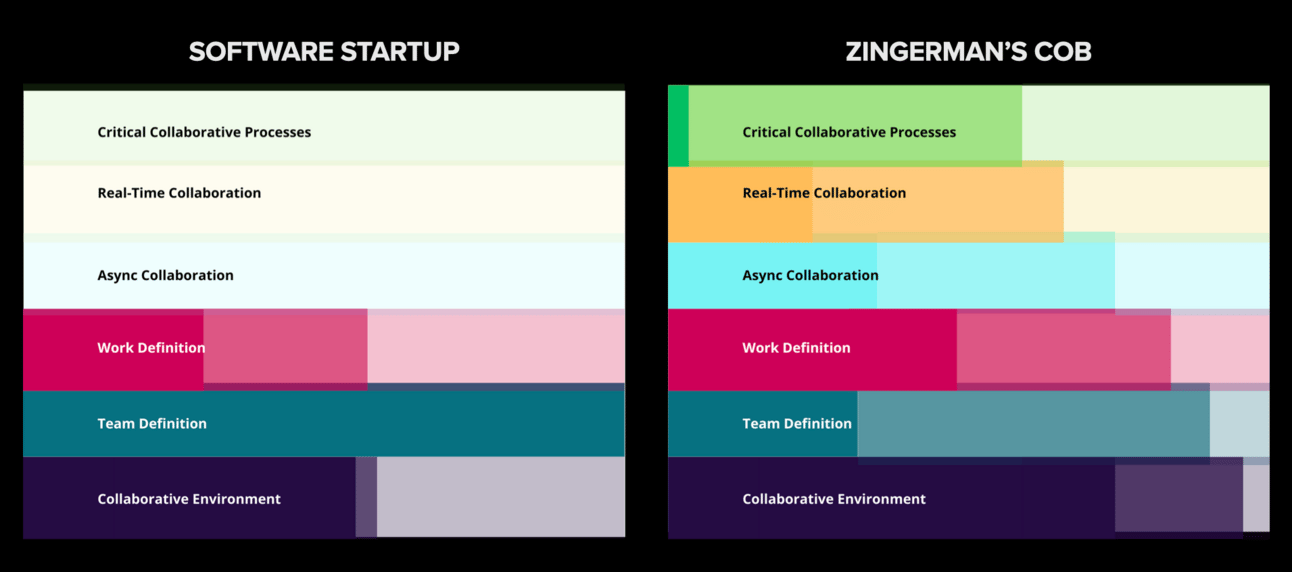

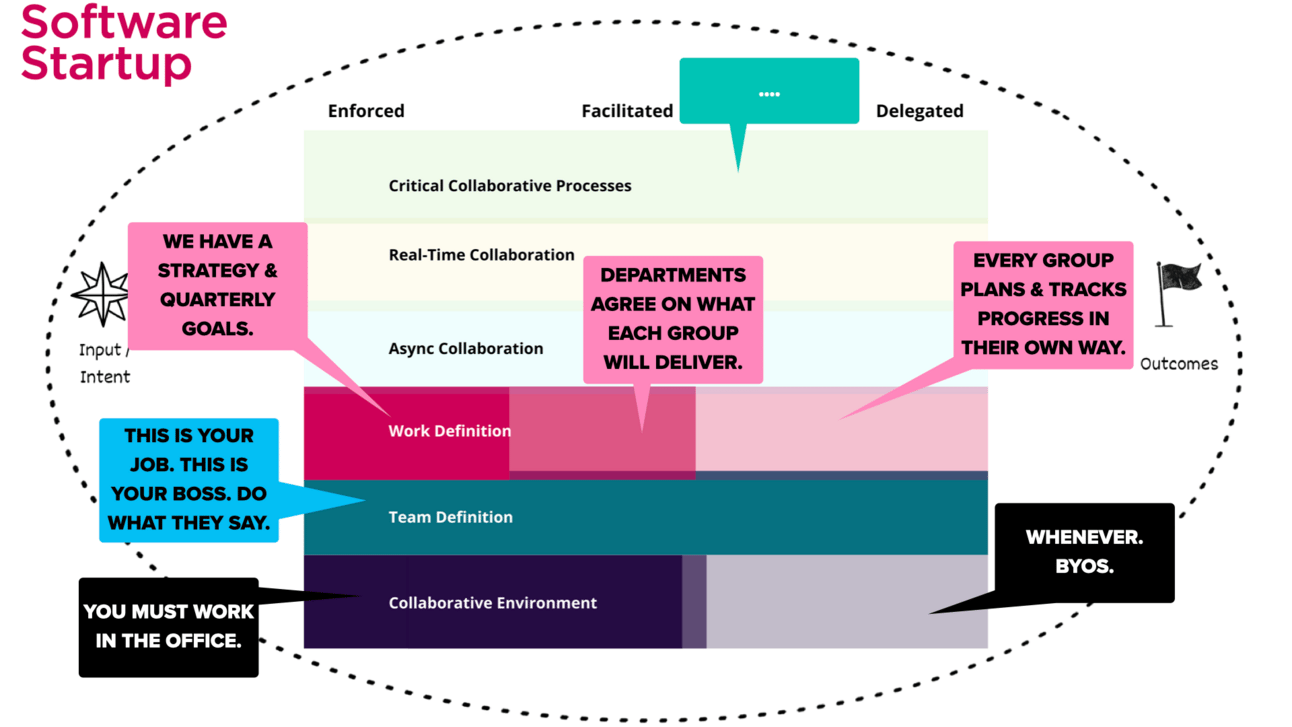

In Practice: The Startup and the Great Place to Work

Here are two examples from my past that illustrate very different approaches to designing collaborative ecosystems, with a sort of "Tortoise and the Hare" lesson.

The Startup

At a young software company, we moved fast and improvised even faster. Leadership set our teams and basic structure but left the rest to department heads. Initially, this freedom allowed us to innovate, but as the company grew, the lack of a cohesive system led to escalating conflicts and dysfunction. Good people left, and the company struggled under its own weight.

Lesson learned: Collaborative ecosystems are living systems—they must adapt or they risk failure.

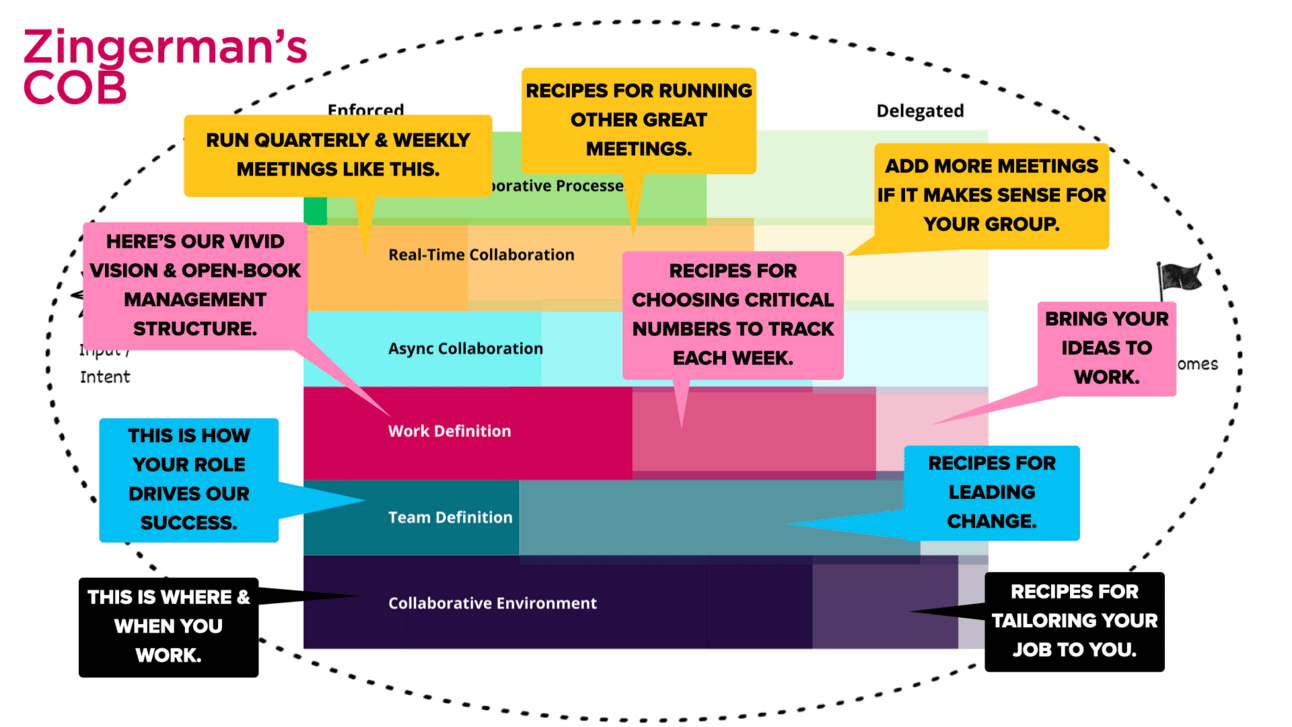

Zingerman's

Contrast that with Zingerman's, a Michigan-based collective of food businesses. I visited them while researching my book on meetings and was struck by their joyful, well-oiled system. (You can read that chapter here.) Their philosophy, 'every cook can govern,' permeates the organization, and over 35 years, they've created a system where positive ripple effects lead to strong business performance, high employee retention, and a stellar reputation.

Takeaway: Zingerman's success shows the power of a carefully nurtured collaborative ecosystem, refined over time.

Most organizations fall somewhere between these examples. They have more figured out than the cock-sure startup and less than lauded great places to work like Zingerman's. That's why it's liberating to realize that...

We Are All Collaboration Ecosystem Designers

Designs are never done, never perfect, and no organization has the time or will to address every possible detail (nor should they.) Collaboration can break down in countless ways, and leaders can’t anticipate every obstacle that might arise.

Instead, we need to equip individuals and teams to notice and close the gaps on their own.

For Individuals, this means ongoing professional development and increased self-awareness.

If you are or aspire to be a collaborative professional, I highly recommend setting up a personal knowledge management system where you capture your design preferences. Check out these articles for ideas about what you might include in your Professional Portfolio and Personal User Manual.

For teams, this means regularly surfacing issues and continuously refining your practices. Teams can embed their solutions directly into the ecosystem or document them in WoW agreements. See our guide to team WoW agreements here.

For organizations, this means ongoing refinement of the overall system.

One useful manifestation of this system is the Organizational Handbook, which acts as a Single Source of Truth people can turn to when they have questions. More on those to come.

I felt we needed a way to visualize and discuss how we design collaboration in our organizations—something that addresses the messy middle ground between our high-level aspirations and prescriptive methodologies. I’m deeply grateful to Dr. Carrie Goucher, Lauren Green, John Keith, and Dave Mastronardi for their invaluable guidance during the development of this approach, and to the leadership cohort at IAF for allowing me to share it with them before making it public.

Now, I want to hear from you. Here's a PDF canvas. Download it, draw on it, take some notes, and let me know.

What ripple effects—positive or negative—have you experienced in your organization? How did they impact your team or culture?

What aspects of this way of thinking through the collaborative ecosystem resonate with your experience? What isn't fitting? What should we consider improving in a future version?

What does this make you want to do differently?

Please share your thoughts and stories—I’m grateful to learn from your experiences. Let’s continue this conversation and refine our ways of working together.

Elise

Did you find this useful? Know someone else who might enjoy it?

Please forward, share, subscribe, and help us spread the word. Thank you!

Interested in bringing us to work with your teams or clients? Get in touch.